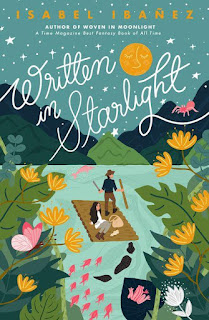

Given her sheltered prior existence, her chances in the wild are not good. The jungle is a treacherous place. Treacherous wild animals are everywhere and even the plants are dangerous. But she is fortunate enough to run across an old friend -- her former guard Manuel -- who still feels loyalty towards her. Together, they battle with caimans and jaguars, and try to stay ahead of the indigenous Illari who are hostile to their presence. Yet it is precisely these Illari to whom Catalina must turn. If she is to regain her throne, she'll need their support.

The Illari, however, want nothing to do with her dynastic squabble and they have something rather more pressing to deal with: a mysterious force that is killing off all life -- human, animal, and plant -- within the jungle. The Illari at first blame Catalina and Manuel for bringing this evil, but the true cause is far more serious and poses an existential threat to the world.

A very lush story that sets fantasy elements within a South American rain forest setting. The adventure moves at a luxurious but utterly satisfying pace as Catalina faces a variety of challenging situations trying to survive in the jungle. A history of forbidden attraction between Catalina and Manuel gives the story some smoldering passion. A romantic triangle opens up when they reach the Illari. It all proceeds swimmingly. Unfortunately, things get really rushed in the last fifty or so pages as a whole new series of facts and characters are introduced. The climax, which develops out of thin air in a breathtaking ten pages, is strongly out of character with the rest of the book and it's hard not to feel like it was a rush job and a cheat.

While it is not acknowledged anywhere, this novel is a sequel to Ibanez's Woven in Moonlight. I suspect that having the full backstory would have made reading this book more enjoyable. Some of the confusing innovations at the end are apparently based on characters and ideas developed in the first book.