At the start of her sophomore year, Celia (like so many heroines of YA novels) is something of a wallflower at Suburban High. But, out of the blue, an uber-stylish clique of kids called "the Rosary" adopt her. She gets a complete life makeover - changing her hair, her clothes, and her social circle. It is a fantasy come true for so many heroines of YA novels. And finnaly, like far too many heroines of YA novels, she discovers the alleged artistic superiority of obscure New Wave bands from the Eighties (more on that later).

But meanwhile at school, things are turning darker that Celia's new outfits. Girls are suffering an unusually large number of freak near-fatal accidents -- always on the day before their sixteenth birthdays. It doesn't matter if they stay home or come to school. In fact, the only thing that seems to protect some girls is losing their virginity. Celia and her chemistry lab partner Mariette don't consider that to be an option. They have a theory about what is causing the accident, and have to move cautiously but purposely towards a solution before their own birthdays come!

It's all over the place story-wise, but actually a nice original story with supernatural themes but an adolescent sensibility (how would you know that black magic was afoot? why, what else would explain why everyone is failing chemistry?). The book is long and really has a few too many moving parts, but it comes together in the end. And while Kotecki is a clumsy writer (particular at the start of nearly every chapter), the creativity and the pace cover his sins. That's a mixed review, but I enjoyed it.

Most of all, what bothered me was that way overused fiction that today's coolest kids would listen to their parents' alternative music. I realize that writers have to write about what they know and that few of them can be bothered to research contemporary music, but get real! Even though I am a child of the 80s myself, I can assure you that the Cocteau Twins, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and the Cure are not gods. And old dudes trying to claim that they are are simply pathetic!

Monday, December 30, 2013

Neverwas, by Kelly Moore, Tucker Reed, and Larkin Reed

Sarah's father has a dream to unite New England, the Confederate States of America, and the free territories of Astoria in a last-ditch effort to defend the Americas against the Nazi Reich of Europe and the Japanese Empire. It's an audacious plan for survival in the early 21st century. It might even work.

Meanwhile, Sarah senses that something is not quite right. Somehow, she remembers a different version of the present, where the American colonists did not lose their war of independence in the late 18th century, and where England was not defeated by the Germans. The answers lie again with the famed Amber House and its mysterious "echoes" of the past.

In the sequel to the surprise wonder of Amber House, the mother-and-daughters writing team of Moore and Reed once again spin an outstanding supernatural tale. The stakes are much higher this time and the story is a great deal more complicated (filled as it is with plenty of paradoxes of time travel), but basically this is another shot at the young female sleuth finding allies (quite literally) in the woodwork. This time, I have to admit that I never quite figured out what was going on, but that didn't stop me from enjoying the ride and I let the story simply take me along with it. With that in mind, this may be a book that rewards handsomely in the re-reading.

Meanwhile, Sarah senses that something is not quite right. Somehow, she remembers a different version of the present, where the American colonists did not lose their war of independence in the late 18th century, and where England was not defeated by the Germans. The answers lie again with the famed Amber House and its mysterious "echoes" of the past.

In the sequel to the surprise wonder of Amber House, the mother-and-daughters writing team of Moore and Reed once again spin an outstanding supernatural tale. The stakes are much higher this time and the story is a great deal more complicated (filled as it is with plenty of paradoxes of time travel), but basically this is another shot at the young female sleuth finding allies (quite literally) in the woodwork. This time, I have to admit that I never quite figured out what was going on, but that didn't stop me from enjoying the ride and I let the story simply take me along with it. With that in mind, this may be a book that rewards handsomely in the re-reading.

Saturday, December 21, 2013

Friday Never Leaving, by Vikki Wakefield

Friday has never felt rooted in any one place. Years of living on the road and in the bush with her nomadic mother ensured as much. But she always had Mom...until she didn't. After her mother dies of cancer, Friday is cast adrift and leaves her grandfather's home for life on the street. Out there, she falls under the spell of a charismatic teen named Arden and a gang of kids that Arden leads. While uneasy around them, the gang gives Friday the sense of family she has been missing. Her years on the road growing up, however, make her more savvy than the others and ultimately brings her into conflict with Arden, with deadly consequences.

The characters are well-developed. It is hard business to develop a large cast of characters and make them vivid enough to distinguish. The kids in the gang are a notably strong cast. And the dynamic between Arden the leader and each of them is complex and interesting.

The book is nicely written, but the story didn't grab me. Wakefield put a lot of effort into her writing, and it shows...sometimes a bit too much. The title (and the cover) are an allusion to a prophecy that Friday will die from drowning on a Saturday (just as all of her female ancestors have). A nice image, but one which is so obvious in its literary pretensions that you trip over it (you know from the first page that drowning will figure in prominently by the end...and are constantly watching out for any mention of water). It's the obvious literary pretensions that make this beautiful book feel lifeless. Too much like a book that you'll be assigned to write a book report on than actually enjoy.

The characters are well-developed. It is hard business to develop a large cast of characters and make them vivid enough to distinguish. The kids in the gang are a notably strong cast. And the dynamic between Arden the leader and each of them is complex and interesting.

The book is nicely written, but the story didn't grab me. Wakefield put a lot of effort into her writing, and it shows...sometimes a bit too much. The title (and the cover) are an allusion to a prophecy that Friday will die from drowning on a Saturday (just as all of her female ancestors have). A nice image, but one which is so obvious in its literary pretensions that you trip over it (you know from the first page that drowning will figure in prominently by the end...and are constantly watching out for any mention of water). It's the obvious literary pretensions that make this beautiful book feel lifeless. Too much like a book that you'll be assigned to write a book report on than actually enjoy.

Flowers In the Sky, by Lynn Joseph

Nina has always been happy with her flower garden and her quiet life in Samana, on the coast of the Dominican Republic. But after her mother catches Nina in a compromising position, mami is determined that Nina will go to New York and live with her older brother Darrio. Darrio has lived in the North for many years, sending a steady stream of money home, and Mom is convinced that Nina will find great fortune there, by marrying a rich doctor or baseball player.

What Nina finds is that life in Washington Heights (where all the Dominican immigrants live) is nowhere as easy as her mother thinks it is. It's a rough life and it takes a while for Nina to make friends and find a place. A young man named Luis with a secret past captures her heart but Darrio doesn't like him and won't explain why. Meanwhile, Darrio has secrets of his own and Nina realizes that the beautiful life of the USA comes with dangers and a dark side.

All of which probably makes the story sound cliche. However, there's a gentleness and honesty to the book that makes it stand out a bit. Nina acclimates to her new environment, but maintains a strong sense of self and a strong moral center (loyalty, beauty, and love) that make her interesting as a person. The story ties up sweetly in the end, but with just enough messiness to make it believable. A good read.

What Nina finds is that life in Washington Heights (where all the Dominican immigrants live) is nowhere as easy as her mother thinks it is. It's a rough life and it takes a while for Nina to make friends and find a place. A young man named Luis with a secret past captures her heart but Darrio doesn't like him and won't explain why. Meanwhile, Darrio has secrets of his own and Nina realizes that the beautiful life of the USA comes with dangers and a dark side.

All of which probably makes the story sound cliche. However, there's a gentleness and honesty to the book that makes it stand out a bit. Nina acclimates to her new environment, but maintains a strong sense of self and a strong moral center (loyalty, beauty, and love) that make her interesting as a person. The story ties up sweetly in the end, but with just enough messiness to make it believable. A good read.

Friday, December 20, 2013

The Lost Girl, by Sangu Mandanna

Eve is an "echo" - a clone of a living person -- created and stored at a sufficiently remote distance for the sole purpose of serving as a replacement if something should happen to the original. Amarra, Eve's "other," lives in Bangalore, while Eve lives in rural England. Eve's job is to study everything that Amarra does and memorize every key fact about Amarra -- in case she has to step in and take over Amarra's life. It's a job that is all encompassing, but largely unfulfilling, as few echos ever need to take up their other's life. And for Eve, whom longs for time to be herself, it has grown unbearable to be enslaved to Amarra's life and be unable to have any life of her own. And then, there is the small problems of "hunters" (vigilantes who oppose the concept of echos and try to find them and kill them) and also growing instability amongst the "weavers" (the three creators of the echos who work at the "Loom" that manufactures them).

Eve's growing self-enlightenment is interrupted when Amarra is killed in an accident. Suddenly, Eve is sent to India to take on the role for which she has been preparing. Despite all of Eve's study, things do not go well as neither she nor Amarra's family are able to adapt to the change. And as Eve, her new family, and Amarra's friends struggle with the situation, it unveils a deep complexity to the issue. Eve may have little choice of the role she has been created to play, but for the family that chose to do this, how do they make it work? And is replacing your deceased daughter with a clone really going to fill the gap in your life?

It's thoughtful and original science fiction. While paying homage to Mary Shelley's classic Frankenstein, Mandanna has created a finely textured study of the meaning of relationships (both friendly and familial) and of loyalty. The book runs a bit long and the ending becomes muddled by a subplot about the weavers that is allowed to achieve too much prominence, but the story is quite fascinating. From the ethical questions of life replacing life as a means to achieve immortality (a topic borrowed from Shelley) to the meaning of self for a clone, there is plenty of thought-provoking stuff here. Finally, it's nice to have some science fiction placed in India. While Mandanna doesn't really explore the local color, it is notable as India doesn't often feature in YA lit (or in sci-fi, for that matter).

Eve's growing self-enlightenment is interrupted when Amarra is killed in an accident. Suddenly, Eve is sent to India to take on the role for which she has been preparing. Despite all of Eve's study, things do not go well as neither she nor Amarra's family are able to adapt to the change. And as Eve, her new family, and Amarra's friends struggle with the situation, it unveils a deep complexity to the issue. Eve may have little choice of the role she has been created to play, but for the family that chose to do this, how do they make it work? And is replacing your deceased daughter with a clone really going to fill the gap in your life?

It's thoughtful and original science fiction. While paying homage to Mary Shelley's classic Frankenstein, Mandanna has created a finely textured study of the meaning of relationships (both friendly and familial) and of loyalty. The book runs a bit long and the ending becomes muddled by a subplot about the weavers that is allowed to achieve too much prominence, but the story is quite fascinating. From the ethical questions of life replacing life as a means to achieve immortality (a topic borrowed from Shelley) to the meaning of self for a clone, there is plenty of thought-provoking stuff here. Finally, it's nice to have some science fiction placed in India. While Mandanna doesn't really explore the local color, it is notable as India doesn't often feature in YA lit (or in sci-fi, for that matter).

A Really Awesome Mess, by Trish Cook and Brandan Halpin

Any book that significantly name drops my alma mater Simon's Rock deserves a special shout out, even if a main character disses the school in the end.

Emmy and Justin have both been involuntarily committed to Heartland Academy, a residential facility for troubled teens. From their own accounts, their offenses seem minor and the punishment is disproportional. However, by the end of the third chapter, the reader can clearly see what their issues are. It takes the rest of the book for the characters to finally admit their problems. Through friendship with the other kids in the program and the experience of adopting a pet piglet, they come to terms with these issues and begin to rebuild their lives.

{An aside: Residential psychiatric programs for teens are an essential literary device in YA lit for getting a bunch of screwed-up teens together without parents (filling the void left by the demise of the boarding school genre). Given how poorly the kids in these stories are monitored, one wonders how the institution survives, but I digress!]

The book is a team effort with Cook and Halpin trading off writing the story (a popular experiment in writing seminars and one that leads to far two many published books). It suffers from a common issue with the format -- a general incompatibility of the writers. The book starts off fine, but Trish Cook's attempts to write a straight story with insight are quickly derailed by Halpin's gonzo writing. He'd rather gross-out the readers and subvert Cook's attempts to build meaningful dialogue and interactions. In her chapters, the story is actually formed, but then Halpin comes in like a typical preschool boy and knocks everything over, leaving things a mess for Cook to dutifully clean up in her next chapter. By the end, I cringed each time I started to read Halpin's chapters (fearing what damage he would do). It wasn't cute and it wasn't interesting. It was simply plain dumb. Maybe Cook should write her own books instead?

And I think Emmy missed out by not going to the Rock!

Emmy and Justin have both been involuntarily committed to Heartland Academy, a residential facility for troubled teens. From their own accounts, their offenses seem minor and the punishment is disproportional. However, by the end of the third chapter, the reader can clearly see what their issues are. It takes the rest of the book for the characters to finally admit their problems. Through friendship with the other kids in the program and the experience of adopting a pet piglet, they come to terms with these issues and begin to rebuild their lives.

{An aside: Residential psychiatric programs for teens are an essential literary device in YA lit for getting a bunch of screwed-up teens together without parents (filling the void left by the demise of the boarding school genre). Given how poorly the kids in these stories are monitored, one wonders how the institution survives, but I digress!]

The book is a team effort with Cook and Halpin trading off writing the story (a popular experiment in writing seminars and one that leads to far two many published books). It suffers from a common issue with the format -- a general incompatibility of the writers. The book starts off fine, but Trish Cook's attempts to write a straight story with insight are quickly derailed by Halpin's gonzo writing. He'd rather gross-out the readers and subvert Cook's attempts to build meaningful dialogue and interactions. In her chapters, the story is actually formed, but then Halpin comes in like a typical preschool boy and knocks everything over, leaving things a mess for Cook to dutifully clean up in her next chapter. By the end, I cringed each time I started to read Halpin's chapters (fearing what damage he would do). It wasn't cute and it wasn't interesting. It was simply plain dumb. Maybe Cook should write her own books instead?

And I think Emmy missed out by not going to the Rock!

Friday, December 13, 2013

The Next Full Moon, by Carolyn Turgeon

Nearly thirteen, Ava is turning into a swan. But, while the phrase may be metaphorical for most girls, for Ava it's quite literal. She's growing feathers and gaining the ability to transform herself into a large bird. And even how to fly.

At the same time, she's discovering that the changes in her body that were once made her feel gangly and ugly, now give her beauty. And where she once was awkward with others, she is gaining grace.

It's a nicely written story and pleasant, but it's hard to escape the issue that there's not much new here. The metaphor of becoming a swan itself is a tired trope and the story (girl experiences transformation, gets together with dream boy, and reunites with long-lost mother -- sorry, it's so obvious that saying it here is hardly a spoiler) is very well-trod. Perhaps it can be enjoyed for the beauty of the story and for the way it captures succinctly the specific moment of being on the verge of adulthood, but it seemed tame and unadventuresome to me. As a coming-of-age story, the fantasy elements were distracting. As a fantasy, it was underdeveloped.

At the same time, she's discovering that the changes in her body that were once made her feel gangly and ugly, now give her beauty. And where she once was awkward with others, she is gaining grace.

It's a nicely written story and pleasant, but it's hard to escape the issue that there's not much new here. The metaphor of becoming a swan itself is a tired trope and the story (girl experiences transformation, gets together with dream boy, and reunites with long-lost mother -- sorry, it's so obvious that saying it here is hardly a spoiler) is very well-trod. Perhaps it can be enjoyed for the beauty of the story and for the way it captures succinctly the specific moment of being on the verge of adulthood, but it seemed tame and unadventuresome to me. As a coming-of-age story, the fantasy elements were distracting. As a fantasy, it was underdeveloped.

Sunday, December 08, 2013

Imperfect Spiral, by Debbie Levy

While babysitting five-year-old Humphrey, Danielle loses sight of him for a moment, he runs into the street, and is fatally struck by a car. At first, Danielle cannot remember the details of the accident and is frustrated by a sense that she was responsible for Humphrey's death. Her guilt is compounded by her inability to speak up (an issue with stage fright that predates the accident). But when the community blames both bad traffic controls and illegal immigrants for the tragedy, she searches for the courage to speak out and set the record straight.

A muddled novel that has a hard time deciding whether it wants to be about celebrating life and grief or if it wants to be a polemical work about immigration. In the book's blurb, the subject of immigration never comes up, but in the afterword, it is all the author can talk about. One suspects that Levy wrote one thing and got led astray by the other (although which thing?). Regardless, the two themes don't mesh very well and the result is the lack of a clear focus to the story that ultimately distracts from its power.

A muddled novel that has a hard time deciding whether it wants to be about celebrating life and grief or if it wants to be a polemical work about immigration. In the book's blurb, the subject of immigration never comes up, but in the afterword, it is all the author can talk about. One suspects that Levy wrote one thing and got led astray by the other (although which thing?). Regardless, the two themes don't mesh very well and the result is the lack of a clear focus to the story that ultimately distracts from its power.

Friday, December 06, 2013

Nothing But Blue, by Lisa Jahn-Clough

A girl finds herself walking down the street with no memory of her immediate circumstances. Someone has died and she must get away! Voices haunt her and danger seems to lurk everywhere. So, she lays low and tries to survive on the street, with help from random strangers and an uncannily intuitive dog. As time passes, her memories slowly come back to her.

I really like Jahn-Clough's spare writing style. Her other two novels are both on my very short list of perfect books. This one is also well-written, but the story didn't work for me. There are a couple of explanations for this. Maybe it is because it is too predictable (memory loss stories have a pretty standard dramatic arc). Or maybe it is because the novel's length relies solely upon having a main character who turns down rescue repeatedly (a choice that always seems to me more designed to extend the story than to serve a literary purpose). It is, in sum, a short story stretched out into a thin novel. It could easily have been resolved in thirty pages and maybe should have been.

I really like Jahn-Clough's spare writing style. Her other two novels are both on my very short list of perfect books. This one is also well-written, but the story didn't work for me. There are a couple of explanations for this. Maybe it is because it is too predictable (memory loss stories have a pretty standard dramatic arc). Or maybe it is because the novel's length relies solely upon having a main character who turns down rescue repeatedly (a choice that always seems to me more designed to extend the story than to serve a literary purpose). It is, in sum, a short story stretched out into a thin novel. It could easily have been resolved in thirty pages and maybe should have been.

This Is What Happy Looks Like, by Jennifer E Smith

Graham and Ellie met completely by accident when Graham mistyped the address of an email and reached Ellie instead of his pig sitter. By random chance, they hit it off and traded emails back and forth. But after months of chatting, Graham has decided to tempt fate and come to Ellie's town to meet her. And she is in for a big surprise!

No, Graham isn't some creepy 46 year-old guy who reads YA literature in his free time. He's actually Graham Larkin -- major teen hottie and up-and-coming young actor. He's easy on the eyes, famous, rich, sensitive, Ellie's age, and miraculously available. And Ellie is just a plain small town girl from Maine, so she is presumably as out of his league as the readers of this book.

But everyone is not quite who they seem. Graham's heart of gold belies his fame and his decidedly simple small-town tastes. And Ellie? Well, you'll have to read the first 120 pages or so to find out what her special secret is because I'm not going to spoil that secret!

In many ways, this is over-the-top romantic teen fantasy (hot famous guy falls for normal girl). He's famous but no one understands his true needs except her, and so he is willing to lavish all of his attention on her. Not that the complete lack of a realistic fiber in this tale makes the story any less fun. Who doesn't like a story about two totally nice people meeting and falling in love? The story is adorable and you'll be happy while reading it.

But Jennifer? Check your map: what part of Maine is located one hour south of Kennebunkport? If that's where the town of Henley is, then it's somewhere in Massachusetts! :)

No, Graham isn't some creepy 46 year-old guy who reads YA literature in his free time. He's actually Graham Larkin -- major teen hottie and up-and-coming young actor. He's easy on the eyes, famous, rich, sensitive, Ellie's age, and miraculously available. And Ellie is just a plain small town girl from Maine, so she is presumably as out of his league as the readers of this book.

But everyone is not quite who they seem. Graham's heart of gold belies his fame and his decidedly simple small-town tastes. And Ellie? Well, you'll have to read the first 120 pages or so to find out what her special secret is because I'm not going to spoil that secret!

In many ways, this is over-the-top romantic teen fantasy (hot famous guy falls for normal girl). He's famous but no one understands his true needs except her, and so he is willing to lavish all of his attention on her. Not that the complete lack of a realistic fiber in this tale makes the story any less fun. Who doesn't like a story about two totally nice people meeting and falling in love? The story is adorable and you'll be happy while reading it.

But Jennifer? Check your map: what part of Maine is located one hour south of Kennebunkport? If that's where the town of Henley is, then it's somewhere in Massachusetts! :)

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

The Sin-Eater's Confession, by Ilsa J. Bick

In the midst of serving as a medic in war-torn Afghanistan, Ben recalls the events surrounding the violent death of his friend Jimmy back home in the rural town of Merit, Wisconsin. Despite the fact that he witnessed the murder, he was unable at the time to come forward and still doesn't really know what happened. That failure to protect Jimmy, before his death or after, drives Ben to deep despair and he struggles with the doubts it implanted in his mind.

An intense psychological exploration of guilt and personality formation. And definitely not a cheery piece! I wanted to hate it for its depiction of rural Wisconsin as some sort of redneck bayou country, but ultimately Bick's depiction of the town Merit was nuanced and authentic. The stereotypes (beer, brats, and the Pack) come mostly from Ben and are not borne out by the actual actions of the characters. In fact, the entire novel bucks convention painting a world that is full of infinite shades of gray and less full of certainty than a reader is comfortable with. Chief among the uncertainties is Ben himself, who struggles with almost every part of his story (not least of which is what he truly felt for Jimmy).

It's an ugly book and a story I don't particularly care to read again. Yet, it rang true and one has to admire the artistry of the author and the fine craftsmanship of the novel.

An intense psychological exploration of guilt and personality formation. And definitely not a cheery piece! I wanted to hate it for its depiction of rural Wisconsin as some sort of redneck bayou country, but ultimately Bick's depiction of the town Merit was nuanced and authentic. The stereotypes (beer, brats, and the Pack) come mostly from Ben and are not borne out by the actual actions of the characters. In fact, the entire novel bucks convention painting a world that is full of infinite shades of gray and less full of certainty than a reader is comfortable with. Chief among the uncertainties is Ben himself, who struggles with almost every part of his story (not least of which is what he truly felt for Jimmy).

It's an ugly book and a story I don't particularly care to read again. Yet, it rang true and one has to admire the artistry of the author and the fine craftsmanship of the novel.

Sunday, November 24, 2013

Dancing Naked, by Shelley Hrdlitschka

Sixteen and pregnant, Kia is faced with the most difficult set of decisions in her life. And while she has the support of her family, a social worker, and a kind youth group leader at church, a lot of the weight falls on her shoulders. Week by week, the story tracks the development of her pregnancy and Kia's adventure with the experience.

Despite some subplots about Kia's relationship with the youth leader and her work at a seniors' home, the novel sticks pretty tightly on the pregnancy. And it stays pretty matter-of-fact. This works mostly because pregnancy is an inherently interesting subject and because teen readers will generally relate to Kia's character (who is level-headed but definitely a bit over her head). For many, the nature of the story provides sufficient dramatic tension. In apparent consideration of that reaction, the story leans so hard away from drama and theatrics that it comes across more as non-fiction.

The issue that it raises for me, though, is that this isn't much of novel. In terms of depicting the experience realistically (and thus being educational), the book deserves praise, but it's a bit cold and clinical. We know that Kia struggles with the decisions about whether to carry the pregnancy to term and whether to give the baby away for adoption, but we really never get inside her head. Thus, the emotional attachment to the character doesn't develops. Perhaps the most insightful part is the book's actual title (an allusion to exposing yourself entirely to the world), but in that sense we never really get to see Kia dance naked (at best it's about as fuzzy as the book's cover).

Despite some subplots about Kia's relationship with the youth leader and her work at a seniors' home, the novel sticks pretty tightly on the pregnancy. And it stays pretty matter-of-fact. This works mostly because pregnancy is an inherently interesting subject and because teen readers will generally relate to Kia's character (who is level-headed but definitely a bit over her head). For many, the nature of the story provides sufficient dramatic tension. In apparent consideration of that reaction, the story leans so hard away from drama and theatrics that it comes across more as non-fiction.

The issue that it raises for me, though, is that this isn't much of novel. In terms of depicting the experience realistically (and thus being educational), the book deserves praise, but it's a bit cold and clinical. We know that Kia struggles with the decisions about whether to carry the pregnancy to term and whether to give the baby away for adoption, but we really never get inside her head. Thus, the emotional attachment to the character doesn't develops. Perhaps the most insightful part is the book's actual title (an allusion to exposing yourself entirely to the world), but in that sense we never really get to see Kia dance naked (at best it's about as fuzzy as the book's cover).

Sunday, November 17, 2013

The Paradox of Vertical Flight, by Emil Ostrovski

My Alma Mater (Vassar) has contributed a fair number of YA writers to the world (most notably Emily Jenkins/E Lockhart). Here comes a new one...

Jack is interrupted in the midst of a suicide attempt brought on by existential angst with a phone call from his ex-girlfriend, Jess. She's about to give birth to their baby and - out of the blue - asks him to be at the hospital with her. That reunion doesn't go so well, but Jack is so struck by the momentous idea of being a father that he decides to kidnap the baby. A madcap road trip to take the baby to meet Jack's grandmother ensues with Jack, his best friend Tommy, and Jess and the baby in tow.

Very much the boy book, the novel is liberally littered with scatological and raucous humor, some implausible adventures and a fair amount of irresponsible and illegal behavior. There's a fair amount of the razzing that passes for male bonding and the girl definitely gets short changed as a character. In case you don't get it, I'm not a fan of the genre but occasionally feel obligated to read a book intended for young male readers.

But Ostrovski has other higher (and contradictory) ambitions for this novel. Jack is a philosophy aficionado, names the baby Socrates, and engages in long imaginary discourses with the child throughout the book. This mental masturbation is fairly dull (and I studied philosophy at Vassar just like the author!), largely irrelevant to the plot, and really far out of character. The topics of the conversations might thrill an undergrad, but since Jack is supposedly a high schooler, it's a little hard to believe that he would have the knowledge to know these topics (even if he's a bright kid, how many high school teachers can expound intelligently on Nietsche?). The literary conceit simply didn't work and it fills a great deal of pages (particularly towards the end). Might have been better in an adult novel, but it hangs on awkwardly and will search hard for an audience.

Jack is interrupted in the midst of a suicide attempt brought on by existential angst with a phone call from his ex-girlfriend, Jess. She's about to give birth to their baby and - out of the blue - asks him to be at the hospital with her. That reunion doesn't go so well, but Jack is so struck by the momentous idea of being a father that he decides to kidnap the baby. A madcap road trip to take the baby to meet Jack's grandmother ensues with Jack, his best friend Tommy, and Jess and the baby in tow.

Very much the boy book, the novel is liberally littered with scatological and raucous humor, some implausible adventures and a fair amount of irresponsible and illegal behavior. There's a fair amount of the razzing that passes for male bonding and the girl definitely gets short changed as a character. In case you don't get it, I'm not a fan of the genre but occasionally feel obligated to read a book intended for young male readers.

But Ostrovski has other higher (and contradictory) ambitions for this novel. Jack is a philosophy aficionado, names the baby Socrates, and engages in long imaginary discourses with the child throughout the book. This mental masturbation is fairly dull (and I studied philosophy at Vassar just like the author!), largely irrelevant to the plot, and really far out of character. The topics of the conversations might thrill an undergrad, but since Jack is supposedly a high schooler, it's a little hard to believe that he would have the knowledge to know these topics (even if he's a bright kid, how many high school teachers can expound intelligently on Nietsche?). The literary conceit simply didn't work and it fills a great deal of pages (particularly towards the end). Might have been better in an adult novel, but it hangs on awkwardly and will search hard for an audience.

Saturday, November 16, 2013

Velvet, by Mary Hooper

It's the Turn of the Century and Velvet is sure that her fortunes are about to change. She ekes out a living in London as a laundress, working long hours in back-breaking labor. So, when one of her wealthy customers, Madame Savoya, offers her the opportunity to join her household as an assistant, she thinks her dreams have been realized and she accepts the promotion without a second thought.

Her new mistress is a medium and Velvet is introduced the arcana of seances and spiritualist sessions. Velvet's never given much thought to "the other side" (as Madame calls it), but she notices early on the great comfort that communicating with the deceased bring their grieving relatives. It is only later that Velvet begins to notice suspicious events and begins to question the motives of her new employer.

Another richly documented historical novel from Hooper. Picking up some related material from Fallen Grace, we get a thorough introduction to the Edwardian obsession with the occult and some of the unsavory practices of the era. There is the expected attention to detail in clothing and dining, as well as a lot of information about everyday life in London. The story is a bit predictable, but Hooper unfolds the story well and the pace is lively. Combined with the well-developed setting, this is a satisfying read.

Her new mistress is a medium and Velvet is introduced the arcana of seances and spiritualist sessions. Velvet's never given much thought to "the other side" (as Madame calls it), but she notices early on the great comfort that communicating with the deceased bring their grieving relatives. It is only later that Velvet begins to notice suspicious events and begins to question the motives of her new employer.

Another richly documented historical novel from Hooper. Picking up some related material from Fallen Grace, we get a thorough introduction to the Edwardian obsession with the occult and some of the unsavory practices of the era. There is the expected attention to detail in clothing and dining, as well as a lot of information about everyday life in London. The story is a bit predictable, but Hooper unfolds the story well and the pace is lively. Combined with the well-developed setting, this is a satisfying read.

You Look Different in Real Life, by Jennifer Castle

Ten years ago, Justine and four other kindergartners were placed around a table and interviewed on film in what was to become Five at Six - a groundbreaking documentary about growing up. Five years later, the filmmakers returned and produced a second installment, Five at Eleven. Now, it's time for a third visit to the kids. However, in the intervening five years, things have changed dramatically and the inseparable children have become sullen adolescents with hidden dramas that they no longer want to share with the world (for Justine, it is the nagging feeling that all the promise she showed

at eleven has fizzled into nothing and she has become unremarkable and unworthy of the attention). The filmmakers' initial attempts to reignite the chemistry between the kids falls flat. But then a crisis occurs that brings the five together again and helps them come to terms with what drove them apart.

What starts as an interesting premise (more on that below) turns fairly conventional as the crisis that pops up mid-book turns this potentially deep study of changing priorities in adolescence and the process of coping with fame, into a predictable kids-hit-the-big-city adventure. At that point, the book for me becomes dull and unremarkable. A series of challenges brings the kids back together again into a tighter bond and Justine finds her special talent. It's all very Disneyesque.

The draw of this book for me was really the premise itself. I'm a big fan of Michael Apted's Up series (the obvious inspiration for this story). Last year, I had the opportunity to watch a screening of 56 Up where Nick Hitchon (who lives near me) was in the audience. He was seeing the film for the first time and afterwards spoke about the experience with the audience. What I learned from him was how emotionally wrenching it is to be part of the film and what difficulty the participants go through every seven years. It made a deep impression and I was interested to learn how Castle would approach this fertile material.

In the first couple of chapters where Justine is struggling with whether she'll participate or not and where she recounts the embarassments of being in the film, I heard a great echo of what Nick had told us and thought that I was going to get a lot out of the novel. However, apparently it wasn't enough to sustain Castle. The shift into high gear action addresses the issue of the separation between the kids and ties up some loose ends from their past, but we never really revisit Justine's (or any of the other children's) ambivalence towards the project. That's really a shame as it was the most unique and original part of this story.

What starts as an interesting premise (more on that below) turns fairly conventional as the crisis that pops up mid-book turns this potentially deep study of changing priorities in adolescence and the process of coping with fame, into a predictable kids-hit-the-big-city adventure. At that point, the book for me becomes dull and unremarkable. A series of challenges brings the kids back together again into a tighter bond and Justine finds her special talent. It's all very Disneyesque.

The draw of this book for me was really the premise itself. I'm a big fan of Michael Apted's Up series (the obvious inspiration for this story). Last year, I had the opportunity to watch a screening of 56 Up where Nick Hitchon (who lives near me) was in the audience. He was seeing the film for the first time and afterwards spoke about the experience with the audience. What I learned from him was how emotionally wrenching it is to be part of the film and what difficulty the participants go through every seven years. It made a deep impression and I was interested to learn how Castle would approach this fertile material.

In the first couple of chapters where Justine is struggling with whether she'll participate or not and where she recounts the embarassments of being in the film, I heard a great echo of what Nick had told us and thought that I was going to get a lot out of the novel. However, apparently it wasn't enough to sustain Castle. The shift into high gear action addresses the issue of the separation between the kids and ties up some loose ends from their past, but we never really revisit Justine's (or any of the other children's) ambivalence towards the project. That's really a shame as it was the most unique and original part of this story.

Saturday, November 09, 2013

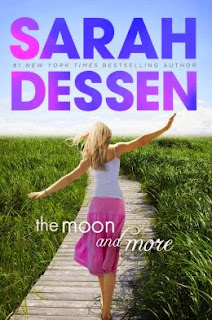

The Moon and More, by Sarah Dessen

In her last summer before college, Emaline has a lot of decisions to make. Living in the small coastal town of Colby, there aren't too many opportunities, but she wants to reach for anything she can. And she's looking for encouragement wherever she can find it.

Her life has been defined by her relationship with her (adoptive) Dad and her (biological) Father. Dad has always been there for her but not been too ambitious, while Father showed up only infrequently but pushed her to succeed. At the same time, Father's let her down recently, bailing on her just as she almost realized her career dreams. A similar tension develops when Emaline meets ambitious Theo, in town to help on a documentary about a local artist-celebrity, and she chooses him over her long-term safe boyfriend Luke.

It's a summer beach story with a complicated storyline: Emaline sorts out these complicated relationships she has with men and tries to figure out how to realize her dreams.

Sarah Dessen is a fantastic writer, with a major talent for expressing emotion and turning beautiful prose out in (increasing-longer) novels. She also creates complicated and realistic young women on the cusp of adulthood like no one else in the literary world today. No one should doubt her talent. But, while Suzanne Collins can decimate a population and overthrow entire regimes in 400 pages, Sarah Dessen can barely get her heroine around the block of a small coastal Carolina town in the same space. To say that barely anything really happens in the story might be overstating things (lots of stuff happens between chapters), but Dessen hates writing action sequences. She would rather do all her action in recap and kill forests of trees in service to dialogue and emotional responses to the (off-screen) action. That isn't all bad (and the focus on emotion is a trademark - and stereotype - of chick lit), but is seems a bit of a cop out when you're reading a 440 page book.

Emaline is an amazingly well-developed character. Perfect for a sleepover and maybe a new BFF, but she doesn't really do very much in this story. And, like so many other Dessen heroines, she's terribly autonomous and isolated. That's all to be expected, but most of the time, it's interesting. Here, I feel like I've read this character before and seen better. In sum, it's another Dessen installment, but not one of the best of the lot.

Her life has been defined by her relationship with her (adoptive) Dad and her (biological) Father. Dad has always been there for her but not been too ambitious, while Father showed up only infrequently but pushed her to succeed. At the same time, Father's let her down recently, bailing on her just as she almost realized her career dreams. A similar tension develops when Emaline meets ambitious Theo, in town to help on a documentary about a local artist-celebrity, and she chooses him over her long-term safe boyfriend Luke.

It's a summer beach story with a complicated storyline: Emaline sorts out these complicated relationships she has with men and tries to figure out how to realize her dreams.

Sarah Dessen is a fantastic writer, with a major talent for expressing emotion and turning beautiful prose out in (increasing-longer) novels. She also creates complicated and realistic young women on the cusp of adulthood like no one else in the literary world today. No one should doubt her talent. But, while Suzanne Collins can decimate a population and overthrow entire regimes in 400 pages, Sarah Dessen can barely get her heroine around the block of a small coastal Carolina town in the same space. To say that barely anything really happens in the story might be overstating things (lots of stuff happens between chapters), but Dessen hates writing action sequences. She would rather do all her action in recap and kill forests of trees in service to dialogue and emotional responses to the (off-screen) action. That isn't all bad (and the focus on emotion is a trademark - and stereotype - of chick lit), but is seems a bit of a cop out when you're reading a 440 page book.

Emaline is an amazingly well-developed character. Perfect for a sleepover and maybe a new BFF, but she doesn't really do very much in this story. And, like so many other Dessen heroines, she's terribly autonomous and isolated. That's all to be expected, but most of the time, it's interesting. Here, I feel like I've read this character before and seen better. In sum, it's another Dessen installment, but not one of the best of the lot.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Taken, by Edward Bloor

It's twenty years in the future and the world is socially and geographically segregated much more clearly into rich and poor. The poor struggle to survive, have poor access to healthcare or education, and generally live in shantytowns. If they are lucky, they have landed jobs as service workers for the rich or have joined the military. The rich live in gated communities, surrounding themselves with armed guards, and lie in constant fear of kidnappers. Kidnapping has become big business and every child from the wealthy families is a target.

Charity certainly knows about the kidnappings. From a few friends who have been nabbed to the training she received in school (she even wrote a paper about it in school!), she understands what to do if you are taken away if you want to stay alive. So, when she wakes to find herself strapped down to a stretcher on an ambulance far away from safety, she calmly accepts that she has been taken. Now, it is a simple matter of waiting for things to take their usual course (a ransom will be paid and she will be let go). However, when things don't go according to plan, Charity realizes that it could all end up badly.

This one's a bit darker than Bloor's other novels (which compared to Story Time is really saying something!). While mildly satirical, Bloor aims here for overt social critique. With a pretty heavy hand, he speaks to inequality, racism, and the arrogance of the haves towards the have nots. The result is fairly preachy and a bit hard to digest (mixing reality and outlandish fantasy in a way that probably disengages readers more than agitating them). The aim is probably to reach an adolescent audience, but the message is not just loud, it's also muddled. Given the polemic, characterizations suffer too, so this isn't such a successful outing.

Charity certainly knows about the kidnappings. From a few friends who have been nabbed to the training she received in school (she even wrote a paper about it in school!), she understands what to do if you are taken away if you want to stay alive. So, when she wakes to find herself strapped down to a stretcher on an ambulance far away from safety, she calmly accepts that she has been taken. Now, it is a simple matter of waiting for things to take their usual course (a ransom will be paid and she will be let go). However, when things don't go according to plan, Charity realizes that it could all end up badly.

This one's a bit darker than Bloor's other novels (which compared to Story Time is really saying something!). While mildly satirical, Bloor aims here for overt social critique. With a pretty heavy hand, he speaks to inequality, racism, and the arrogance of the haves towards the have nots. The result is fairly preachy and a bit hard to digest (mixing reality and outlandish fantasy in a way that probably disengages readers more than agitating them). The aim is probably to reach an adolescent audience, but the message is not just loud, it's also muddled. Given the polemic, characterizations suffer too, so this isn't such a successful outing.

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

37 Things I Love, by Kekla Magoon

Two years ago, Ellis's father was injured on the job and fell into a coma. He's never woken up. Every day, when Ellis isn't visiting him to vent her life's frustrations, she's fighting with her mother about whether they should turn off his life support. Mom believes it is time to let go, but Ellis can't accept that and she fights bitterly to keep the machines going. In thirty-seven brief chapters, Ellis tells us about the things she loves and simultaneously about the last week of her sophomore year, when everything changes and she has to confront the decisions she has made and to reevaluate her friendships and loyalties.

A brief, but ultimately satisfying story about relationships and letting go. Magoon focuses her attentions on her heroine and gives us a well-developed emotional landscape, but one where everything (and everyone) else is incidental. Ellis herself is engaging and interesting enough to get the reader hooked. However, given the brevity of the story, it is inevitable that the other characters get shortchanged. From the friends and family to a host of throwaway supporting characters (the neighbor, the counselor, etc.), there is really only space for Ellis here. This works well in this case and the novel is successful in its modest ambitions.

A brief, but ultimately satisfying story about relationships and letting go. Magoon focuses her attentions on her heroine and gives us a well-developed emotional landscape, but one where everything (and everyone) else is incidental. Ellis herself is engaging and interesting enough to get the reader hooked. However, given the brevity of the story, it is inevitable that the other characters get shortchanged. From the friends and family to a host of throwaway supporting characters (the neighbor, the counselor, etc.), there is really only space for Ellis here. This works well in this case and the novel is successful in its modest ambitions.

Princess Academy: Palace of Stone, by Shannon Hale

In this long-overdue sequel to Princess Academy, Miri and the girls of Mount Eskel have come to the capital Asland to help their Britta prepare for her wedding to Prince Stephan. It's exciting for Miri to finally see the city that they have only heard about before. Everything is so much grader than they have ever seen before! But their arrival comes at an inopportune moment. Unrest is afoot and a revolution is beginning to stir. On their first day, an assassination attempt on the king is barely averted before their eyes.

The unrest is directed at the rulers, but Mount Eskel itself is in a precarious position. As Mount Eskel's delegate Katar explains to Miri, it is critical that they (as the newest members of the kingdom) position themselves well, regardless of the outcome. To that end, she entrusts Miri with the task of finding the rebellion and ingratiating herself with its leaders (dangerous and tricky when one of your own is about to marry the King's son!). Through what seems like luck, Miri succeeds in the task when she befriends a young idealistic student named Timon. But Miri gets more than she wished for. At first, Miri is personally very taken by the goals of justice and equality for which the revolutionaries are fighting. She finds herself drawn to Timon and even begins to question her attachment to her simple boyfriend Peder from home. But as the situation grows dark and dangerous, Miri discovers that she is trapped in her new subversive role. And being a revolutionary means not only plotting against the King, but also betraying her friends and homeland. As the masses start to rise up, Miri finds that she must tread carefully through a series of difficult decisions to stay alive and protect her home.

It's all a bit darker than the original story. Hale has drawn a great deal from the history of the French Revolution to show how dangerous uprisings are and how easy it is to get caught in the crossfire. The novel itself is an engrossing tale of politics, intrigue, and loyalty. In her usual style, the grownups are generally helpless and stubborn, so it falls on the adolescents to rise to the occasion and save the land. That is convenient for the story, but it also provides a pleasing dramatic arc as Miri fully comes into her own.

This is truly a magical work which expands the potential of YA fantasy literature!

The unrest is directed at the rulers, but Mount Eskel itself is in a precarious position. As Mount Eskel's delegate Katar explains to Miri, it is critical that they (as the newest members of the kingdom) position themselves well, regardless of the outcome. To that end, she entrusts Miri with the task of finding the rebellion and ingratiating herself with its leaders (dangerous and tricky when one of your own is about to marry the King's son!). Through what seems like luck, Miri succeeds in the task when she befriends a young idealistic student named Timon. But Miri gets more than she wished for. At first, Miri is personally very taken by the goals of justice and equality for which the revolutionaries are fighting. She finds herself drawn to Timon and even begins to question her attachment to her simple boyfriend Peder from home. But as the situation grows dark and dangerous, Miri discovers that she is trapped in her new subversive role. And being a revolutionary means not only plotting against the King, but also betraying her friends and homeland. As the masses start to rise up, Miri finds that she must tread carefully through a series of difficult decisions to stay alive and protect her home.

It's all a bit darker than the original story. Hale has drawn a great deal from the history of the French Revolution to show how dangerous uprisings are and how easy it is to get caught in the crossfire. The novel itself is an engrossing tale of politics, intrigue, and loyalty. In her usual style, the grownups are generally helpless and stubborn, so it falls on the adolescents to rise to the occasion and save the land. That is convenient for the story, but it also provides a pleasing dramatic arc as Miri fully comes into her own.

This is truly a magical work which expands the potential of YA fantasy literature!

Monday, October 28, 2013

Story Time, by Edward Bloor

When Kate and her uncle George (who is two years younger than her) find out that they have been accepted into the Whittaker Magnet School, they have opposite reactions. George is excited. It is just the sort of environment where he can finally spread his wings and excel. He's managed to score the highest score on the school's entrance exam ever. And the school's focus on standardized testing plays to his strengths. Kate, on the other hand, is no genius and the change of schools will prevent her from auditioning for Peter Pan this year. Kate's mother languishes in depression, while her grandparents (George's parents) are lost in their floor-shattering clogging practices.

Regardless of initial impressions, the school itself proves to be a nightmare. It teaches quite literally to the test, subjecting its students to continual bubble-filling, brain-enhancing drinks, and rote memorization (and phonics!) for the younger kids. The school is a conglomeration of everything that is wrong in modern schooling. And all of this before accounting for the demon that is possessing people on the school grounds or the disastrous visit from the First Lady of the United States!

A bit long and not nearly as funny as Tangerine, Bloor still has a good time making bitter fun of the American education system. Younger readers may find the chaos to be great fun in itself, but even middle readers will recognize the satire. Taken seriously, the book (with numerous serious injuries and sundry dead bodies) is grotesque, but it works wonderfully if you don't get too literal with any of it. Unfortunately, that is where the problem of length sets in. Being a satire, we don't have any attachment to the characters. Instead, the story rests on humor. The wit gets a bit tired after the first 200 pages. By the 400th page, we're more than ready for it to wrap up!

Regardless of initial impressions, the school itself proves to be a nightmare. It teaches quite literally to the test, subjecting its students to continual bubble-filling, brain-enhancing drinks, and rote memorization (and phonics!) for the younger kids. The school is a conglomeration of everything that is wrong in modern schooling. And all of this before accounting for the demon that is possessing people on the school grounds or the disastrous visit from the First Lady of the United States!

A bit long and not nearly as funny as Tangerine, Bloor still has a good time making bitter fun of the American education system. Younger readers may find the chaos to be great fun in itself, but even middle readers will recognize the satire. Taken seriously, the book (with numerous serious injuries and sundry dead bodies) is grotesque, but it works wonderfully if you don't get too literal with any of it. Unfortunately, that is where the problem of length sets in. Being a satire, we don't have any attachment to the characters. Instead, the story rests on humor. The wit gets a bit tired after the first 200 pages. By the 400th page, we're more than ready for it to wrap up!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)